Adapted from Volume Three of All Night Menu.

1.

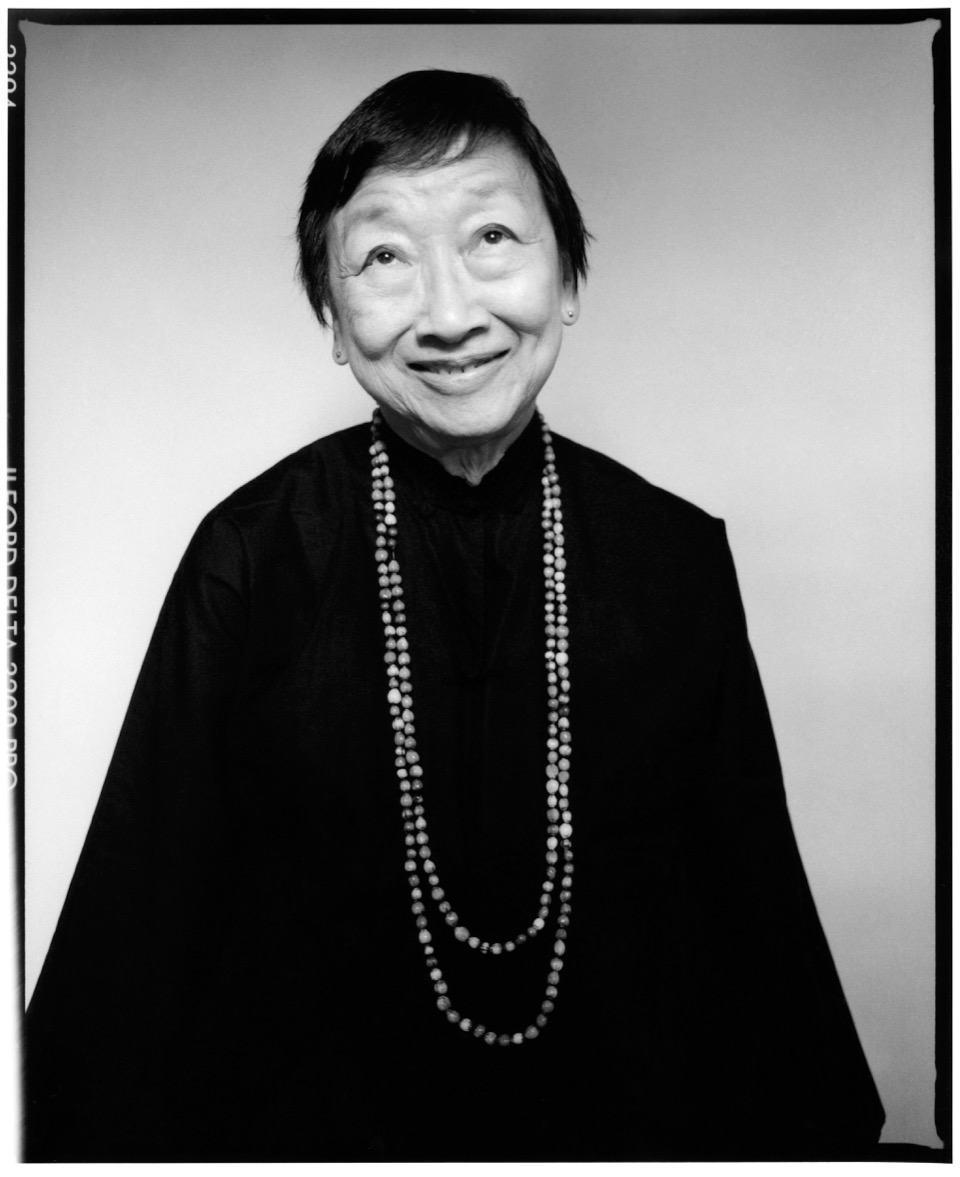

She was raised by uncles and aunts in the back of Sunrise Laundry, 1220 W. 9th Street, between downtown and MacArthur Park. Each morning before school she and her four siblings ate warm congee and dumplings alongside four employees who shuttled dirty laundry to the big industrial washers near Old Chinatown. Clean clothes were returned to 9th Street to be pressed and folded. As kids, Helen Liu Fong and her siblings spent their afternoons turning socks.

When she was 12, the school counselor at Virgil Junior High asked what she wanted to be. “An architect,” Helen said. After school, she had to ask her best friend, a Japanese girl named Mary, what an architect did. The year was 1939. “I think they design houses,” she said. “Or homes.”

Her grades got her into UCLA, and then UC Berkeley. A degree in city planning led to her hiring as a secretary in the firm of Eugene Choy, the first Chinese-American from Southern California to be licensed by AIA. When Choy downsized in 1951, Helen joined Louis Armet and Eldon Davis, a pair of USC architecture grads whose business was taking shape in the adjoining office. Both firms worked out of a small professional building at 1334 Wilshire, three blocks north of Sunrise Laundry.

2.

George and Rena Panagopoulos operated Yum Burger on Manchester Ave. and Holly’s on Hawthorne Blvd., but they coveted a location that would capitalize on the exit traffic from LAX, which had grown following Pereira & Luckman’s spectacular “space age” redesign. Prior to the opening of the 405 and the 105, cars leaving the airport took La Tijera north onto La Cienega, which channeled them through the hills of the Inglewood Oil Field and back down into central Los Angeles. When the triangular traffic island formed by La Tijera, La Cienega, and Centinela became available, the “Poulos” family jumped on it.

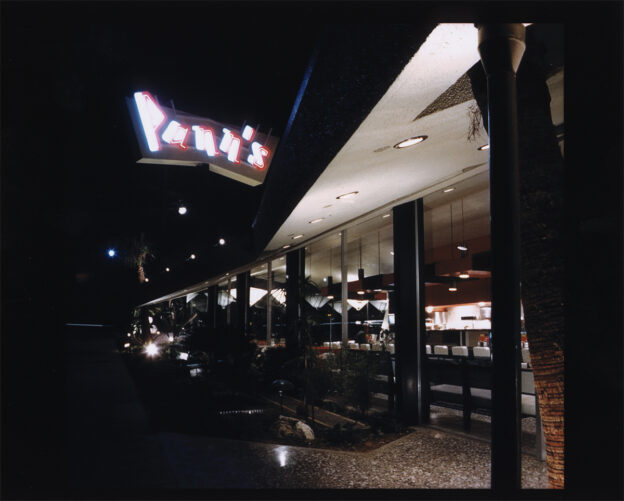

Like every Armet & Davis diner, Pann’s was designed to seduce motorists from a passing glance. The exterior walls were glass curtains that revealed huge glowing triangular pendant lamps. It could have been a Cadillac showroom. From the outside, it looked as spacious as a church and as mesmeric as an aquarium. Helen said each coffee shop should always appear like the site of a special event, even if the only movement within was a transient sipping coffee on a swivel stool.

Norm’s, Ship’s, and Johnie’s drew policemen and high schoolers, loners and laborers, retirees and double-daters. The plunging rooflines and totemic neon lured drivers off the road, the interiors had to deliver sensory pleasure on a much more intimate scale. Customers ate cheeseburgers and pie on chairs designed by Charles and Ray Eames; checked the time on George Nelson clocks; nestled between booth dividers by Van Keppel-Green. These were the touches of Helen Fong. She was their invisible curator, gifting modern design to people who would never step foot in a case study home.

3.

In the ‘60s, Denny’s and Bob’s Big Boy purchased franchise templates from Armet & Davis. As far-flung states imported the California Coffee Shop, Los Angeles began demolishing the originals. “During recent months, the trend in coffee shop design has been to more formality,” Eldon Davis told the Los Angeles Times in 1964. “This means a more subdued décor, carpeted dining areas screened from the counter-and-booth sections, more formal appointments, and in some there will be a bar.”

Before Pann’s was set to open on March 6, 1958, Helen stopped by for a final inspection. Everything was perfect, down to the cast-resin screen that Hans Werner and Betsy Hancock had created for the foyer: an abstract map charting the journey of the Poulos family from Tripoli to Inglewood. “But this,” Helen, stopping at the wall of one-inch square white tiles that fronted the cook’s line, “just won’t work.” It exemplified the cold sameness that Pann’s was designed to cure. Helen pulled a vial from her purse and used the bottle’s tiny brush to coat several tiles.

The doors opened the next day and never closed. In decades to come, every other coffee shop that Armet & Davis built in the 1950s was demolished or remodeled beyond recognition. Only the one on La Tijera remained unchanged, protected by a few dabs of Helen Fong’s ruby red nail polish.