This roundtable discussion took up a topic fundamental to L.A.’s understanding of its own history yet in many ways underscrutinized outside the academy: the ways that whiteness as a racial category and as a mark of privilege or elite status has been constructed, defined, reshaped, taken advantage of, and elided in Southern California as the region has grown. Multiracial since its founding in 1781, Los Angeles is a city where categories of racial privilege and oppression have arguably been more fluid than in other parts of the country, and where whiteness, especially during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was sometimes one of several racial or ethnic categories that could confer status or privilege. This panel, featuring scholars who have devoted much of their careers to work in this area, sought to explore precisely this kind of complexity in defining the relationship between whiteness and civic memory in Los Angeles. Natalia Molina: The first question is about how we see the constructions and meanings of whiteness and how they’ve played out in L.A. history. Can you tell us a little bit about how whiteness has played out in your work specifically, and how these issues continue to reverberate into the present? And please note that while this panel is about whiteness, we invite you to discuss in your answers the people and places in Los Angeles that contest whiteness and white supremacy, both historically and in the present.

Eric Avila: I’ll jump in by laying out a ground rule for discussing whiteness in Los Angeles. I think we all know from our work that L.A. has always been multiracial, multicultural, and multiethnic. Whenever whiteness comes into the conversation, I think there’s always the danger of taking it as a thing for granted, as if it’s this kind of ahistorical, a-geographical construct. I want to make sure that I avoid that trap. And for me, that means thinking about the many different groups from different parts of the world who have sought inclusion into this paradigm of whiteness. What is it about L.A., about the timing of L.A.’s development, about the spatial and geographic character of Southern California, that enabled certain groups to access privileges, spaces, and identities of whiteness, and at the same time excluded others? In my opinion, this puts African Americans in the typical position of being the other of all others—the group by which or against which other racial and ethnic groups have sought to define their whiteness.

Jessica Kim: We think a lot about race, and the construction of race, in Los Angeles in terms of the city’s immense diversity, created by many immigrant streams. And that’s incredibly important. But there’s also a need to think about the construction of whiteness as it relates to L.A.’s position in the Pacific world. Many L.A. historians talk a lot about boosters.01 The “booster” era of L.A. spanned roughly 40 years (1885–1925), during which “rough-hewn and optimistic pioneering city leaders worked with creative writers, real estate barons, and artists to bring new settlers and new businesses” to town, creating a narrative that “often rewrote the city’s history and present situation to suit their idealized, European-American values.” See Hadley Meares, “‘Sunkist Skies of Glory’: How City Leaders and Real Estate Barons Used Sunshine and Oranges to Sell Los Angeles,” Curbed Los Angeles, May 24, 2018.

They were key in the city’s growth, and they really thought of themselves as positioned within this broader Pacific world and within American imperial projects in Latin America and Asia. So these immigrant streams into Los Angeles make, in some ways, the construction of race and whiteness in L.A. unique. But the ways in which Angelenos constructed whiteness was also positioned in the broader Pacific world and in the relationship between American imperial exploits and race. Race-making was outward-looking and transnational.

Brenda Stevenson: Being a person from the American South, what I’m always struck by with regard to Los Angeles and Los Angeles history is the way in which whiteness has been framed by the American South. While I look at L.A. as being part of the international world and part of the Pacific too, it is also a place that is parochially white. By that I mean, when I look at the ways in which whiteness is presented in the American South, particularly historically, it’s also presented that way in Los Angeles. Once the quote-unquote Americans gained control of California, African Americans who were migrating to Los Angeles and the American West at the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries were quite aware of that—that this was the way whiteness was defined. As a more recent migrant to Los Angeles, I came at a moment when Los Angeles was being promoted nationally and around the world as “the most diverse city in the United States.” And that, to me, it really hid whiteness, hid the social and political and economic problems associated with whiteness vis-à-vis other groups of people. People would talk about how diverse L.A. was, as if that meant equitable, as if that meant inclusive. And it didn’t mean that. It absolutely did not mean that.

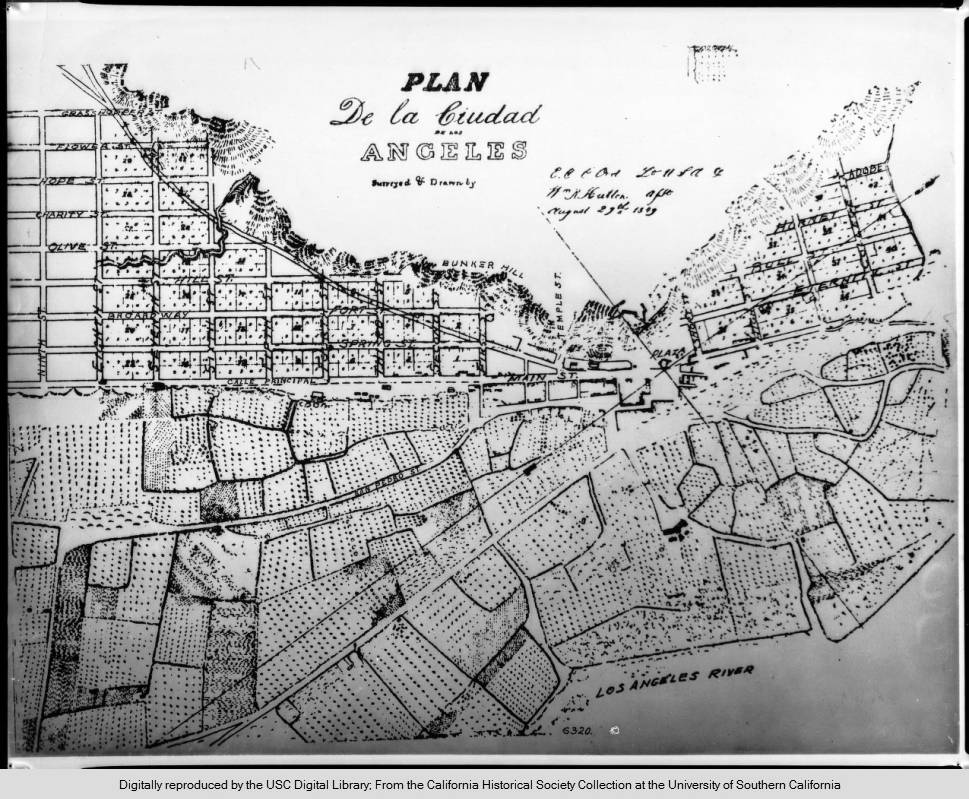

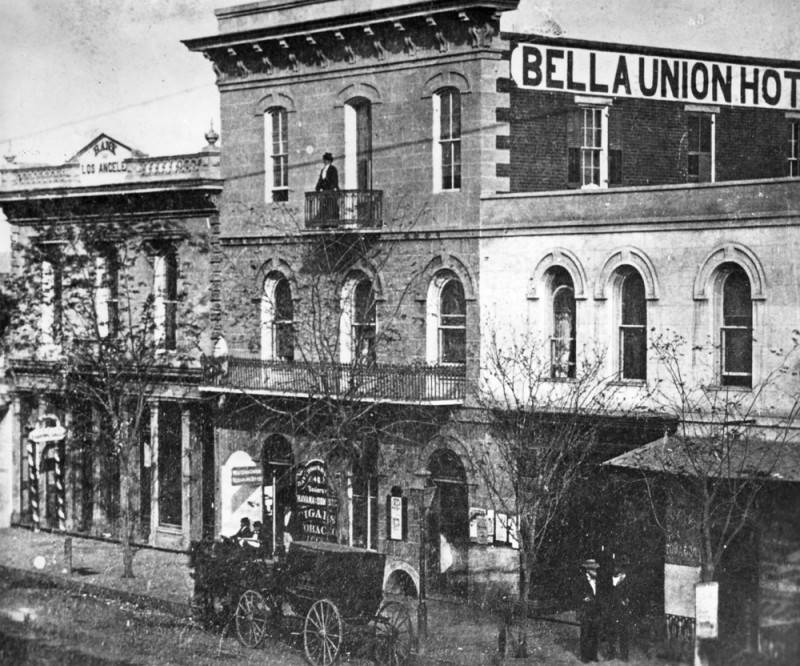

David Torres-Rouff: As a person who studies early Los Angeles history, one interesting thing is that unlike other places in the United States, whiteness is one of many categories of racial supremacy in the early history of Los Angeles. For maybe 70 years, whiteness was not the most important racial category in Los Angeles. Being “an Español” or a “gente de razón” during the Spanish era, or Californio/Californiana during the Mexican period and into the 1870s, meant far more than being white. And one of the interesting things about Los Angeles is that whiteness as an idea was an immigrant, brought west across the United States. This gives slightly different contours to the history of whiteness in Los Angeles.

Wendy Cheng: In terms of the past and the identity of the city, I’ve been thinking a lot about the “narrativization” of Los Angeles history. One ongoing narrative is of white racial innocence. This idea of multiculturalism that Brenda raised has been part of this idea of inclusion: that if we include more stories, therefore we will somehow have a better or fuller or more accurate understanding of the history of Los Angeles. But actually, we have to change the entire framework of that narrative to attack and deconstruct this idea of white racial innocence, or neutrality. That’s been something that’s on my mind a lot, because that’s often the surface that is not scratched. Those narratives of white racial innocence continue to be selected over and over.

As a geographer, I’ve also been thinking a lot about how whiteness has been and continues to be spatialized in Los Angeles, and what effects that has. In the work my coauthors Laura Pulido and Laura Barraclough and I did for A People’s Guide to Los Angeles,02 Laura Pulido, Laura R. Barraclough, and Wendy Cheng, A People’s Guide to Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

we learned how thoroughly white-dominated spaces continue to stand in for L.A. as a whole: gentrified downtown, Hollywood, the west side. There is careful and nuanced work that historians have done, of course, but in the popular representations of L.A., it’s still downtown to the west side standing in for Los Angeles as a whole. And maps literally stopping right before they get to South L.A. or East L.A. or any other part of what many of us would understand as greater L.A.—the real L.A. And yes, we understand L.A. in the present as a multicultural city, but the dominant narrative of L.A. history is still a blank slate, as a city with no history. And I think the violence of that as a settler-colonial narrative, as a white settler-colonial narrative—one that erases Mexican and Indigenous histories, spaces, and communities—still has yet to be really dealt with in any kind of mainstream way.

BS: I just want to add that when we think about whiteness in Los Angeles, we also have to think about Hollywood. Because Hollywood really establishes for the world, and for the country as well, what whiteness is. It’s really interesting to be talking about whiteness in the place where the major image-maker of whiteness exists. Los Angeles has always come off globally as a kind of sparkling, celebrity-driven white society where everyone’s rich, where everyone’s golden, where everyone’s blonde. That has framed whiteness in Los Angeles in a particular way. Los Angeles produces the images of whiteness that persist throughout the world.

EA: Whenever you talk about race—ideas about race, this race or that race—in my mind you are fundamentally talking about a cultural construct. You’re talking about an ideology. You’re not talking about something that can be measured and mapped empirically. So you have to adjust your thinking to grapple with that. When you’re talking about L.A.’s identity, you are talking about urban identity and how urban identity was racialized. The next question is how that identity is then put into practice—how it’s mapped onto space, grafted onto space, and whatnot. L.A.’s development as a modern, white, American city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries coincided with a revolution—a revolution in communications, a revolution in transportation—that enabled these representations of a white L.A. It began with lithographs. It began with postcards. It began with magazines and catalogs in the late nineteenth century. And Hollywood was the culmination of that cultural process that began earlier, through earlier modes of technological mass reproduction of images and texts. To me, “Birth of a Nation” is kind of the beginning of Hollywood’s intervention of constructing a regional variant of whiteness.03 The Birth of a Nation (original title: The Clansman), directed by D. W. Griffith (Hollywood, CA: David W. Griffith Corp., 1915).

The way I’ve thought about whiteness is as a balance between cultural ideologies, representations, images, texts, and narratives on the one hand, and then structural practices and policies and political economy on the other hand. And the relationship between the two. That’s how David Roediger talks about whiteness. That’s how George Lipsitz and Matthew Jacobson write about whiteness. I think in talking about urban identity, you have to kind of keep those factors in play always, in framing discussions of whiteness.

JK: When we discuss more recent and contemporary identifications of Los Angeles as this multicultural place, that can completely erase people’s lived material realities. We’re still one of the most economically divided cities in the country, and the gap between the rich and the poor is absolutely related to race and racial construction and racial relations. That often gets erased by a celebratory rhetoric of Los Angeles being a multicultural place. Of course it is, and the city’s multicultural past and present are remarkable, but we have to pair celebrations of multiculturalism with critical discussions of the ways in which people of color have historically faced structural and institutionalized inequality.

BS: What Hollywood does is really underscore this notion that if you can’t make it in the United States, it’s your fault. Because look how glittering and wonderful and beautiful all these people are and look at this enormous wealth. Look at all these stories of small-town actresses coming to L.A. and really making it and now living in these glorious mansions. And look at people on basketball teams who become enormously wealthy. So this image of Los Angeles as this place where dreams come true—come true multiracially, not just white dreams but dreams for other people too—it really does deepen the sense of L.A. as a place of adventure, of promise and prosperity. And if you and your racial group don’t find that, then that’s something that’s innately wrong with you and your racial group, because look how it plays out elsewhere in this landscape.

EA: The other critical element is suburbanization, the abundance of undeveloped land to create enclaves of wealth—and enclaves of whiteness—across the class spectrum. And I think that’s where the structure really comes into play, because suburbanization afforded a space to create communities based on the fiction, purported by Hollywood and other agents, of that narrative.

DTR: I have thought a lot about this external image of Los Angeles as a diverse and cosmopolitan space, and maybe even a Brown space. What is served, and what interests are served, by marketing it as such? And what are the ways in which that ideal of Los Angeles doesn’t filter back down? Just like the old version of the Spanish fantasy past never filtered down to the lives of Mexican people, this notion of Los Angeles as a global, shining example of cosmopolitanism and diversity is so much more surface than substance. It’s one more neoliberal fantasy. The disconnect between the image and the reality is borne out in the buildings where people live and work and spatialized in suburbia, in the spaces of inner-city Los Angeles, and behind the scenes in Hollywood. Think about all the people who work in craft services and the thousands of names you see rolling by in the credits, people who make $18 an hour or less and have no profit stake. If we want to think about Hollywood, it conceals a great deal of class and color differentiation even in the production of the movies that give us the Hollywood image.

WC: Absolutely. The two words I just wrote down as you were talking were “power” and “labor.” If you take a step back from those Hollywood productions, you see who’s working on those sets, who’s doing the heavy lifting, who’s doing the service work, who’s bringing the food. Whiteness, even though it is a cultural construct like any other racial idea, can be mapped. And you can see how extremely segregated white people are in Los Angeles. The director of my kids’ preschool, who was a longtime organizer for the Bus Riders Union, she taught me something important this summer: she said that anti-racism is not enough, because people will never fight for something or somebody until they learn to love it first. What that extreme ongoing segregation does is it allows people—particularly white people—to not see people of color. So, yes, L.A. is multicultural, but it’s also hierarchical, it’s also extremely sort of caste-driven. And so it’s not that there are not people of color in those spaces, it’s just that they’re in a particular hierarchy that allows them to not be seen by people in the dominant class. That’s an important way of thinking about how segregation and the socialization of race feed into these geographies, these dominating geographies of whiteness in Los Angeles that are exemplified by Hollywood.

JK: I think Eric mentioned the Spanish fantasy past, and David as well. That’s exactly what was happening in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Los Angeles was being sold as this idyllic place where racial tensions didn’t exist and where, according to the advertising, it was a white space. But all that was based on the work of nonwhite peoples, whether it was Chinese and Japanese immigrants or Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants. That tension is centuries-long in California.

BS: This erasure, when you look at Indigenous peoples, that’s also something that we can map or look at with regard to other imperial forces, as David said. And so when we think about California coming into being, or Los Angeles coming into being, we think about the Spanish Empire. We think about the Mexican Empire. We think about the United States. But there still tends to be, more than anything else, erasure of Indigenous peoples. I think that’s the most invisible group we have in our society. And so when we think about whiteness, and even multiculturalism, there seems to be very little place for these groups of people.

NM: I just want to pause here to recap some of the important issues that you’ve brought up. We’ve talked about whiteness as a social construction, and how it’s been mapped and grafted onto space. And the ways in which these categories were exported to the world by Hollywood. I know for me, in terms of thinking about race as something that is a social construction but also structural, with the growth of the federal government in the 1930s (which could come in with so much money), there is an effort to institutionalize these categories of difference through mapping, through the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps, through redlining. And through that we can see that the cultural is structural. And that continues to play out today.

DTR: I just wanted to emphasize—not that it’s been deemphasized—the connection between race and space and the spatialization of racial identity. Brenda talks about the Spanish choosing to plop Los Angeles—as an idea, formed on paper—right into the middle of a Gabrielino-Tongva village. And we can think about all the ways in which the idea of white supremacy only takes on real meaning when it gets built into and mapped onto space. We can think about this in a really basic way. What would Jim Crow be without the segregated spaces it created, without colored restrooms, without separate drinking fountains and beaches, without the threat of violence along the color line? These ideas don’t actually take on meaning until they come to shape spaces that sort people—in this example, by color.

And I would just point out that we can also look to more recent events to illustrate the ways that we still see the spatial disparities in the city. When the Ballona Creek overflowed in the 1998 El Niño, there was a massive lawsuit about the damage done. And one of the things the City had to do was create a map of all the sewer and storm drain lines in the whole city and grade them. And in this survey, what you can also see is that if you follow the D- and F-graded sewer and storm drain lines and the ones that emit noxious chemicals, they also trace the outlines of every poor Black and Mexican and Southeast Asian neighborhood in the city. And all the ones that have been recently updated and that function well and don’t emit chemicals that risk the public health of the people who live on the ground above them trace really neatly to white neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley, on the west side and in Santa Monica.

These are not only phenomena of the past. They are so literally, physically deep in the infrastructure of the city that getting away from them is not as simple as believing in anti-racism. It actually involves an excavation of the physical space and an effort to make change.

EA: That’s a great point, David. L.A. freeways are monuments to whiteness. Urban renewal, Chavez Ravine—these were federal policies. They had armies of planners and transportation engineers working on this, but you can identify ideological or cultural underpinnings of these practices as they took shape during the post–World War II period. I’m also thinking about Genevieve Carpio’s work and the way that she looks at mobility. Mobility, particularly in a decentralized urban region like Los Angeles, is another venue for the construction of racial identity and racial hierarchy. Her work on police arrests of Mexican drivers, the research I’ve done on highway construction in Boyle Heights, the role of the automobile in shaping this—this brings in not just questions of infrastructure but questions of technology and mobility as well.

JK: To David’s point about environmental racism and infrastructure and a hundred years of that being built into the very way that the city is constructed—how does gentrification layer on top of that? For example, there are dozens of uncapped oil wells across Echo Park, a deeply historically Latinx community. And it’s only now, with the construction of big condo complexes in a rapidly gentrified Echo Park, that this has become a more contentious issue. For a century, those wells just went uncapped. But now that white folks are moving into what were historically nonwhite neighborhoods, it’s an issue that people are paying attention to.

WC: The people who get to be considered the public in L.A., it’s still mentally a white public. I found this a lot in the San Gabriel Valley. You have the city of San Gabriel, with the mission there and this deep attachment to the mission by white San Gabriel Valley residents, and also some Mexican American, Californio, and Tongva/Gabrielino residents as well. But overwhelmingly, that attachment to the mission and the Spanish fantasy past is claimed by white people. In a city that is 60 percent Asian American.

EA: We should also acknowledge the role of the Spanish fantasy past in the regional construction of whiteness. When I teach the Spanish fantasy past in my courses, I often compare it to the minstrel show. I compare it to a regional version of racial appropriation, racial disguise, not necessarily on the stage of a theater but in architecture, in the built environment, in landscape design. As a cultural historian, I come back to questions of performance, of narrative. I think Wendy’s point is an excellent one about creating publics, creating audiences, creating readership. The L.A. Times—great example of white racial formation by creating a readership. I think you can talk about the Spanish fantasy past very much in a similar way.

NM: I feel like we’ve touched on the main historical topics. I’m going to ask that we move on to thinking about what this means in terms of civic memory. Clearly, it ties in very neatly; it does more than just dovetail. But let’s talk about that more explicitly. How does whiteness shape civic memory? What has its role been in the past? What will it be in the future? What is gained or lost by how we remember whiteness specifically when it comes to civic memory? And do civic memory projects provide a vehicle for unspooling whiteness and its central role in ways that other projects do not?

EA: In my own work on whiteness, there’s always been this tension between the people who have said, “Why are you studying this? Don’t you realize that this a concept that needs to be abandoned and forgotten?” And, on the other hand, there are the scholars who say, “We need to explore the construction of—the active making of—whiteness so that we don’t take it for granted.” So when it comes to the issue of civic memory, the question is how is whiteness supposed to be remembered? Or is it supposed to be forgotten? Or is there a way of remembering whiteness that can remind us of its destructive power in American history? This has been an ongoing tension in the scholarly work on whiteness.

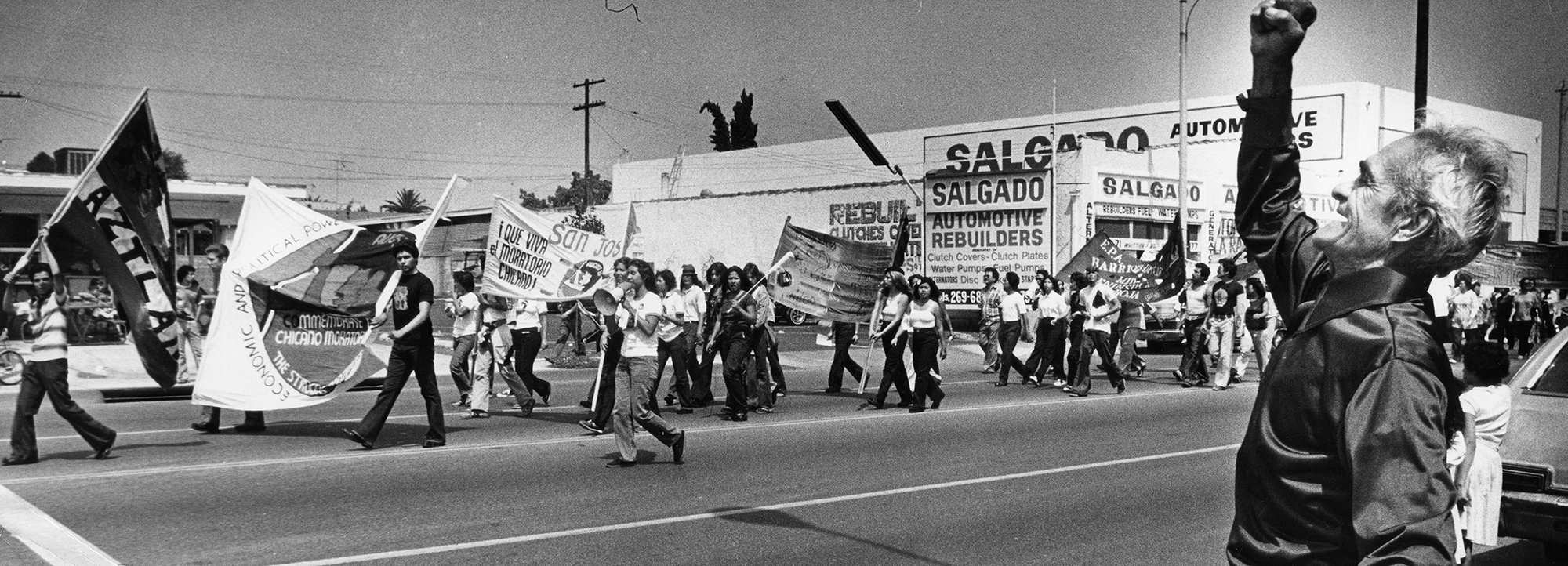

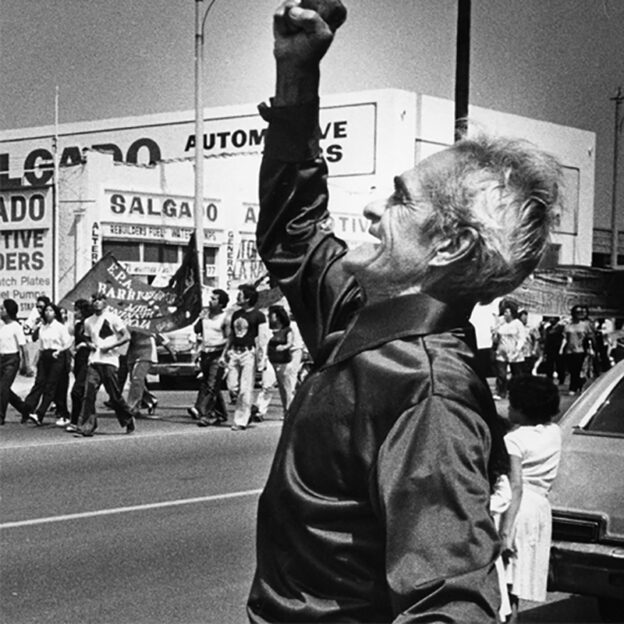

DTR: One thing that’s interestingly embedded in the question “How does whiteness shape civic memory?” is the degree to which whiteness and the civic have been largely synonymous in a popular understanding of Los Angeles for a really long period of time. Before the 1960s or ’70s, whiteness and civic memory were probably really closely aligned. And what the city would choose to remember would be these moments that could validate a narrative of the succession from Spain to the United States, and white supremacy in the United States, without acknowledging Indigenous or other Brown people, or Black people, who lived in the city and worked in the city. We have to dig into how we can untangle whiteness and white supremacy from the understanding of what civic is, and what the representation of Los Angeles is. And how do we smash through this barrier of both the commoditized diversity of L.A. that never really gets down to ordinary people, and the sheen and veneer of Hollywood, writ large, that we’ve talked about at length already.

BS: When we talk about civic memory, we have to focus on public school education, or education in general—the curriculums that talk about Los Angeles history, California history, the history of the American West. As long as we continue to have the fourth-graders doing the mission project, and all these other kinds of things, it’s going to be very difficult to unmask whiteness—the privilege of whiteness.

WC: I was looking at your book, Brenda, about Latasha Harlins [The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins], because I was thinking about the 1992 uprising, and how that idea of white people as neutral bystanders was really powerful in that case. This past summer, Black Lives Matter L.A. consciously tried to intervene in that by staging its protests in the Fairfax district, in Beverly Hills, in gentrified downtown. We have a lot to learn from the younger generation. For example, in Taiwan, the government has a “reverse mentorship” program where they invite a certain number of people under 35 to speak to them. This also came up in our Working Group’s earlier conversations about how the Staples Center was reinvented as a public memorial for Kobe Bryant. That’s a great example of a memorial or monument that expresses who L.A. really is and includes the real public of L.A. I’m trying to think about civic memory in ways that allow us to expand that notion of who the public is and bring different generations in to participate in that. Because I really feel a lot of hope for our younger generations and I feel that they would have a lot to contribute.

JK: We need to think really creatively about memorials that are maybe not lasting but that represent how Angelenos think about civic memory and the history and significance of Los Angeles in the moment. We can create things that may not be there in 10 years. Or even 10 months.

EA: I think there’s a real paradox in this question of civic memory and whiteness. In my reading, whiteness has so much to do with forgetting: forgetting who you are, forgetting where you came from. Letting go of traditions and heritage and language, and perhaps even religion, to fit in or assimilate into this mainstream of whiteness and all the privileges that come with it. So, how do you memorialize the practice and processes of forgetting? I really like what Wendy and Jessica and Brenda have been saying. I also was really struck by the Kobe Bryant example as a kind of civic memorialization from the bottom up. Usually, the whole project of civic memory is driven by elites, by people in charge. So that memorial is something that just really kind of stuck with me.

NM: This conversation is so interesting. It’s very different from the first half of our conversation, which seemed to be about trying to really make visible what has been invisible and show the way that it’s played out structurally, culturally—the way that it’s been mapped onto space. I’m interested in this idea about how we might think about alternate ways of producing civic memory, expanding publics, and anything else that you wanted to touch on that maybe has a different tenor.

BS: Even though we’re looking at new ways of doing it, some of the old ways are good as well. I think people were able to reinvent the Staples Center as this memorial for Kobe Bryant—as Alicia Keys said, “This is the house that Kobe built”—because of what we see has been happening at the Smithsonian Institution and now this push toward a women’s museum. And the new slavery museums that have come up in the American South and the lynching memorial [the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama], and all of that. We’re at a time in which other voices are being supported, even nationally, in some ways after very long, long campaigns by everyday Americans to make this happen. In terms of civic memory, this is a moment where we can also charge those institutions that come out of taxpayers’ dollars to listen to the voices of the people who want to be represented, who should be represented, in these kinds of institutions. And I think that we have to see that some of these institutions like the Southwest Museum [of the American Indian in Los Angeles] for example, like CAAM [the California African American Museum] for example, have been starved in terms of receiving taxpayer monies to develop programming and exhibitions that broaden our sense of what our communities are. I’m glad to see that Tyree Boyd-Pates is at the Autry [Museum of the American West in L.A.]—he left CAAM and went to the Autry—and he’s doing some really interesting stuff on collecting around COVID-19 and also collecting around Black Lives Matter. [See the related essay in this volume by Boyd-Pates, “Glorifying the Lion: Telling the Other Side of L.A.’s History.”] We really do have to continue to push for supporting the institutions that historically have given access to other stories, to other histories, to defining our city in different kinds of ways outside of whiteness—not just creating new things but supporting and allowing those institutions to evolve.

NM: Maybe on that note, in terms of not just shaping new things but allowing what’s already there to evolve, what about memorials in L.A. that already exist? What about those memorials that enshrine and tell the story of whiteness? Are there ways to start a conversation about existing memorials with the work we’ve been doing in the Civic Memory Working Group?

JK: In wrapping up my book project, which was about Los Angeles investors in Mexico in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, I started looking at how many landmarks and places that tourists—and even Angelenos—like to visit because they’re considered beautiful, iconic parts of Los Angeles, and realizing just how many of those had material roots in extractive and imperial projects in Mexico. And so I started thinking about creative ways that we could contextualize Griffith Park, for example, and the fact that Griffith J. Griffith made his money in Mexico. The fact that we have this large urban green space is directly related to taking resources out of Mexico and centering them in Los Angeles. Are there creative ways that we can reflect on the infrastructure and design of early Los Angeles and provide context? Rather than just taking for granted that the city looks the way it does, are there ways to think about how whiteness and race created the spaces we live in?

DTR: One axis in this conversation is about greater inclusivity—that is what Wendy and Brenda talked at length about. The other axis is about entities like the City of Los Angeles being willing to come to terms with the ravages of white supremacy, and to think about how to interrogate existing memorials or to create new memorials that actually begin to unspool these violent, supremacist legacies. Some things should be torn down, but I think there are ways we might productively leave old monuments in the landscape and consider ways to augment them to provoke education in another way. We can use old monument as objects that make us ask questions as opposed to just telling us prepackaged stories. One way is to think about how to start a conversation about existing things, opening up our understanding of civic memory. To go back to what Eric said earlier, if we think about the freeways as a monument to racial capitalism, to white supremacy, to the destruction of countless neighborhoods of people of color, then let’s think about how we can intervene in that. What can we put on every freeway on-ramp, where people sit while it’s metered in the morning on their commutes? People will read it. There are all kinds of opportunities for thinking about that as a new landscape for provoking questions.

EA: It’s not like there isn’t existing signage on the road, but when you look at that signage, it reminds you who has the power to convey their messages and who doesn’t.

NM: I agree with David about some of these interventions, and about augmenting memorials that already exist. I think about the Huntington Library, since I’ve been working with them. You could have signage at the Huntington where you include the history of its workers. I love Jessica’s point about Griffith Park—even when there isn’t a specific memorial, just exploring the questions of how this land came to be. I moved back to Los Angeles two years ago and decided to explore the city by hiking it—the Santa Monica Mountains, Griffith Park. And yes, there are still plaques everywhere within the parks explaining who donated the land. But where did they get the capital to do it? Racial capitalism, that’s where! So I just love these different ideas about really making all that a part of the landscape.

WC: I was thinking about the Mulholland Memorial Fountain. It’s a giant, phallic water fountain dedicated to William Mulholland.<04 Mulholland is credited with creating the infrastructure—in the form of the hugely controversial Los Angeles Aqueduct—that enabled L.A. to become the sprawling metropolis that is did, while rendering the Owens Valley a virtual desert.

It’s such a great opportunity for thinking about technocratic whiteness, white male masculinity, and urban planning. There’s a great documentary that came out recently on the L.A. Aqueduct.05 The Longest Straw, directed by Samantha Bode (Los Angeles: Rainbow Escalator, 2017).

It talks about how this water comes from Paiute land. And Paiute people are still feeling the ramifications of their water being taken from them. And then thinking about the relationship of L.A. to the Owens Valley—that this is L.A. City–owned land, on which Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II and put to work trying to make that land productive. I think that memorial fountain, that space, would make for a really interesting opportunity to try to articulate or enact different ideas about how the memorial is presenting history, versus this fuller and more accurate picture of L.A. history.

BS: One of the things that I’ve thought about is how we can reclaim prison spaces. There’s been a lot of discussion about the prison population in Los Angeles and in California. But how has this land been transitioned over time? Thinking about the transition of Indigenous land to a space where Indigenous people and other people of color are overly represented as prisoners would be something that needs to be part of the civic memory conversation.

WC: I think the memorials are important, but they’re actually just the tip of the iceberg, or whatever phrase we want to use. Any large parcel of land in Los Angeles, any powerful institution, has a history that goes back through those different colonial regimes, with connection between land and power. Think about Dodger Stadium and civic power. Are there ways to build awareness so that people understand how these large parcels of land came to be, and how they’ve been handed down to the elite power holders in each era?

NM: I’ll just add that a lot of this work has been done, it just isn’t prominently displayed. The narratives that we have of Chavez Ravine, the photos have been collected—put those on the freeway off-ramps! Or Rosten Woo’s work on Dodger Stadium and how that land continues to collect money through parking revenue. It goes back to Eric’s point about who has the power to put that story out there.

EA: This is an old theme in L.A. history. L.A. is so fragmented by its own communities that the problem is how to get people on board to support implementing the memories of a different group of people. That’s the challenge in a city like L.A. that is so segmented and so enclaved, and so disparate in the geography of wealth and power. The history of civic memory has been each group in it for itself. And that means that doing really tough groundwork to build cross-community consensus. Okay, these groups have been remembered in some ways; these groups have not. How do you build those bridges to make sure that everyone is on board? That’s a unique challenge when you have a city shaped the way L.A. is shaped.

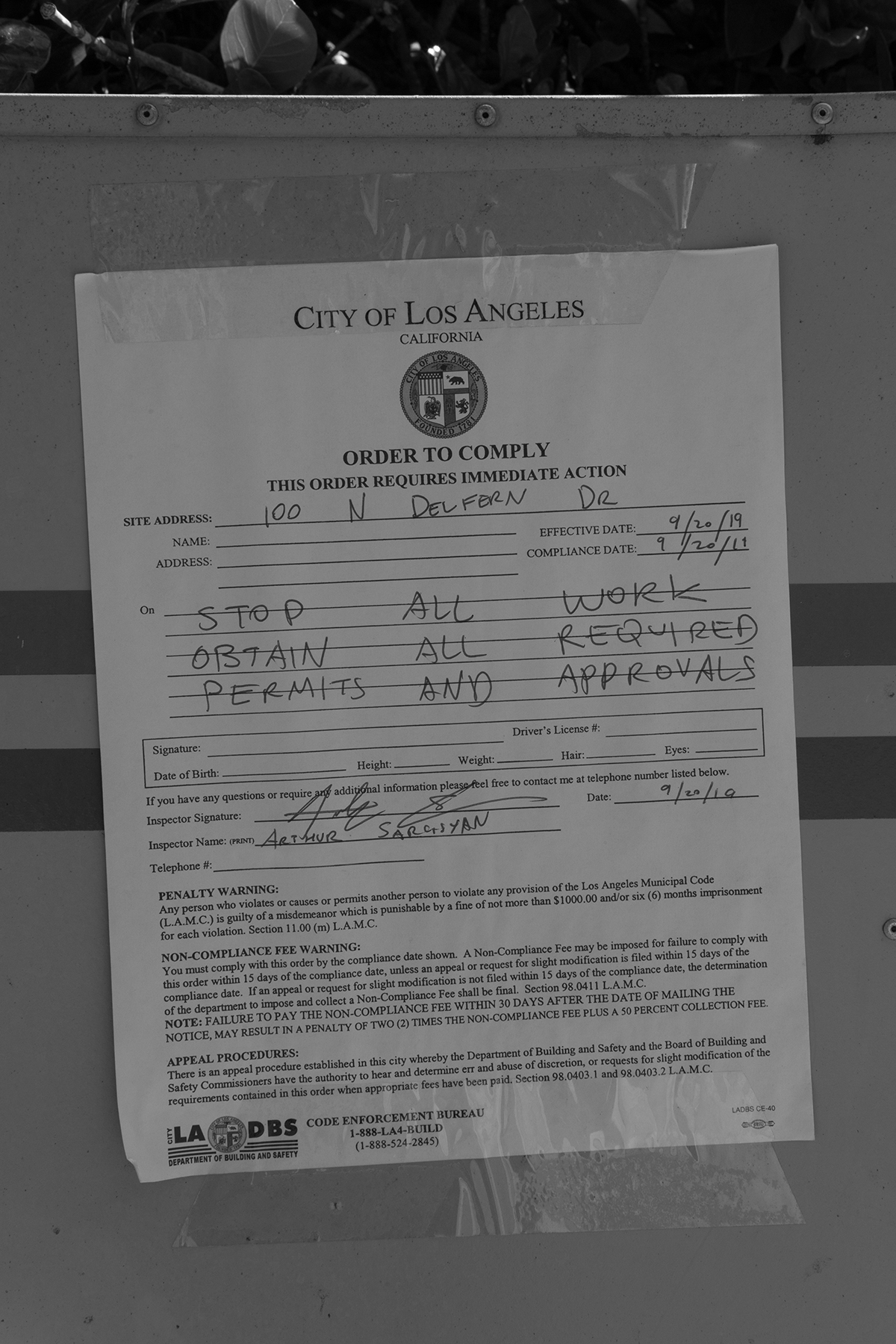

DTR: The other piece of this puzzle has to do with radically shifting the way that the City goes about recognizing places and the process for memorialization. The way it’s set up now, the City is a gatekeeper, a force that sometimes resists the efforts of people to have their spaces recognized. To have the kind of transformation that we have been talking about, the City really has to become a facilitator.

NM: That’s a very powerful note to end on. Thank you so much. Let’s do it again next Friday.