This group considered the ways in which civic memory might be cultivated and brought to material life in Los Angeles. Through synergistic and wide-ranging discussions, we came up with a set of key themes, modes of commemoration, and three “sites/histories” as case studies. The committee agreed that this is an especially potent moment for elevating the stories of both displaced and ordinary Angelenos to send the message that their histories matter in the city today—and will matter tomorrow. It is important to acknowledge and commemorate places that may look or seem ordinary and to take an expansive, inclusive view of historical significance. Commemoration reminds us that history is not a closed chapter, but a living dimension of our social fabric: it reflects our vision of the city’s future. We see this as an auspicious moment to ensure that an ethos of inclusion and social justice is embraced in that vision.

In the text that follows, we summarize the three main areas of our discussion: key historical themes, our ideas on modes of commemoration, and case studies of three sites—or more accurately, “histories,” since they were not all tied to place—that flesh out how these commemorations might take shape. The case studies are meant to serve not only as templates for other sites and stories, but also as conceptual jumping-off points.

Themes

Our group compiled a list of themes in L.A. history that are enduring, defining forces and have shaped Los Angeles. These themes can help create a larger conceptual framework for thinking through the City’s commemoration strategy. The criteria used in identifying them included chronological and geographical breadth and the inclusion of diverse sets of communities. Our list of themes included displacement and removal, migration and immigration, resistance and collective transformation, racial violence, social justice, labor and the people who built L.A., culture and cultural production, caretaking during crisis, Los Angeles as “born global,” and Indigeneity.

Displacement emerged as a particularly resonant theme. The displacement of people from neighborhoods, from land, and from privilege has been a constant throughout Los Angeles history, at least since the arrival of Europeans in the eighteenth century. Community displacement has reflected shifting power and racial hierarchies that could and did lead to racial turnover of spaces across Los Angeles—from ethnic enclaves like Chinatown to residential neighborhoods bulldozed for redevelopment and freeway construction. Displacement is an especially powerful theme because it lives on in the people who carry memories of displacement and who live out lives of resilience. They are part of our social fabric, and honoring their experience, memory, and acts of resilience should be a primary objective of commemoration.

Immigration and migration is a related theme, which can represent displacements not only from home countries but also in the community experiences that both groups confronted in Los Angeles. Immigrants neighborhoods were often targeted for redevelopment, gentrification, or punitive state policies (such as the repatriation of Mexicans during the 1930s or the internment of Japanese during World War II). The myriad ways that displacement appears and reappears throughout L.A. history pose challenges for place-based commemoration, because these are histories of movement, departures, and spatial erasures. They are often sites that no longer exist on the landscape. They comprise what UCLA cityLAB director Dana Cuff has termed “provisional spaces,” where once-vibrant sites might now be parking lots or vacant lots. These provisional sites compel innovative and creative ways of thinking about commemoration.01 Dana Cuff, The Provisional City: Los Angeles Stories of Architecture and Urbanism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

Another theme our discussions foregrounded was resistance and collective transformation. Countless stories of struggle by marginalized groups to resist oppression and claim their right to the city recur throughout L.A.’s past (and present). This theme captures both the nature of that marginalization and how various groups have challenged the forces that marginalized them—racism, class exploitation, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and so on. This resistance can be collective or individual. L.A. history is replete with narratives of people challenging structures of oppression and creating alternative forms of power. These efforts have been waged by people of color, the poor, workers, immigrants, women, LGBTQ individuals, political radicals, environmental justice activists, and other marginalized groups. Their stories have often played out in everyday places—in people’s homes, in the streets, in nondescript buildings. As the writers of A People’s Guide to Los Angeles put it, these histories require “an appreciation for vernacular landscapes—landscapes of the ordinary and everyday” since those were often the spatial contexts of these efforts.02 Laura Pulido, Laura R. Barraclough, and Wendy Cheng, A People’s Guide to Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 7.

These two themes—displacement and resistance—resonated with our group, and we used them as launch points for discussing how the City might imagine commemoration around their frameworks.

Modes

Our group also brainstormed ideas about modes of commemoration—how the City might recruit people’s interest in civic memory. These modes fell roughly into three categories: permanent installations, internet tools, and ephemeral installations and activities. The conceptual framework of a theme like displacement, for example, demands flexible, creative thinking about how to capture something that no longer exists in space. While our site examples flesh out these modes in more detail, we wanted to convey the substance of our discussion on modes since it touched on several ideas that might be deployed beyond our examples.

Permanent markers might include statues, murals, plaques along a sidewalk or in front of a building, patterned markings in a sidewalk to trace the trail of a historic space or event (such as a protest march), or other fixed markers. New statues could be commissioned that would bring to light important, little-known figures in L.A. history, or an unknown figure to stand in for a significant movement or moment. We also discussed existing statues that might be creatively recontextualized. The group agreed that permanent statues can be problematic, as we have witnessed in the tearing down of controversial statues (most recently Junípero Serra’s). Contextualization offers an alternative to removal.

One compelling example comes from the Bayreuth Festspielhaus in Germany. Outside that opera house sits a bust of Richard Wagner, created by the pro-Nazi sculptor Arno Breker in the 1950s. After years of discussion about whether to take down that sculpture, in 2012 an exhibition was installed surrounding the bust, consisting of panels that profiled the Jewish musicians who were forbidden to perform at the Festspielhaus during the Nazi regime (many of whom fled Germany or were killed in the death camps). What began as an almost accidental, temporary solution to the problem of the Wagner bust ended up creating a moving, powerful space for reflecting on these layers of history.03 See Vincent Vargas, “2012 Bayreuth exhibition: ‘Silenced Voices,’ YouTube, June 6, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dMsRG44uvuE.

A similar approach might lend itself to contextualizing controversial monuments in Los Angeles.

Internet tools are powerful instruments for working flexibly across L.A.’s vast geographic spaces and for their ability to create an augmented reality to help people experience their city in new ways. Apps offer the pragmatic advantage of circumventing property owners who might otherwise be reluctant to affix something permanent to their property. One idea that we discussed is a navigation-based “L.A. sites of memory” driving app: as the user drives around the city, a narrator could tell histories of the places being passed. Driving apps could also be structured as thematic tours, guiding users from one site to the next. Tours could be devised around topics like labor history, African American activism or culture, LGBTQ history in L.A., or environmental justice (the tours in A People’s Guide to Los Angeles are an excellent starting point).

There might also be an “LA sites of memory” app linked to light rail lines, where stories of places along the line routes would come up on a rider’s phone. Schools and community colleges along these routes might be recruited to help write these stories and provide content and ideas. Likewise, walking tour apps could focus on particular neighborhoods, protest march routes (such as the Chicano Moratorium or the 1994 marches protesting Prop 187), or other areas significant to L.A. history. An app could also act as a central hub, showing where all civic memory activities are located throughout Los Angeles—driving tours, light rail apps, walking tours to schedules of events, and so forth. In line with these tours, a “pilgrimage menu” might be developed for the 2028 Olympics, to guide visitors to L.A. to explore the hidden spaces and histories of the city. Community members might be enlisted to help identify these places and develop these histories, and tours could be created out of this work.

Models for these types of interactive app experiences exist. The Cleveland Historical app, for example, was developed collectively by historians, students, and community members through the Center for Public History + Digital Humanities at Cleveland State University. The app, which is available on both the Apple and Android platforms, links places to archival images, oral histories, audio clips, and documents. Other examples abound, from Google Earth virtual tours to GyPSy Guide’s audio tour guides and more.04 Cleveland Historical app website, undated, https://clevelandhistorical.org; Shianne Edelmayer, “Google Earth Tour Guide: 14 Virtual Tours You'll Want to Check Out,” MakeUseOf, May 18, 2020; GyPSy Guide Audio Tour Guides website, undated, https://gypsyguide.com.

Ephemeral modes of commemoration are another medium. These might include temporary installations, performances, projections, bus tours, or other events. Intangible modes lend themselves well to themes like displacement, where physical structures no longer exist. “Intangible heritage” is, in fact, one of the most controversial, critical debates in heritage conservation at the moment, as practitioners debate whether the imperative is to preserve extant buildings that looked the way they did during their moment of historical significance, or to emphasize how people interacted with those places beyond the four walls of a building.05 Works that capture the debate on “intangible heritage” include Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa, eds., Intangible Heritage (London: Routledge, 2008); Mike Buhler, Desiree Smith, and Laura Dominguez, “Sustaining San Francisco’s Living History: Strategies for Conserving Cultural Heritage Assets,” San Francisco Heritage, September 2014, https://www.sfheritage.org/Cultural-Heritage-Assets-Final.pdf; Donna Graves, James Michael Buckley, and Gail Dubrow, “Emerging Strategies for Sustaining San Francisco’s Diverse Heritage,” Change Over Time 8, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 164–85. On intangible cultural heritage, see also the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) website, https://ich.unesco.org.

San Antonio and San Francisco have been experimenting with “intangible heritage,” and this may be an auspicious moment for Los Angeles to consider doing the same. In San Francisco, for example, communities created cultural districts as “special use” districts to protect legacy businesses, nonprofits, and other cultural institutions in existence 30 years or more.06 “Process for Establishing Cultural Districts,” San Francisco Planning Department, Executive Summary, Administrative Code Text Amendment, June 6, 2018.

These efforts protect the uses of these neighborhoods and their historic memory, while combatting displacement and gentrification.

Modes such as intangible commemoration and heritage can push us to find innovative ways to cultivate civic memory for Los Angeles. For instance, projections of images on a building create an augmented reality, prompting passersby to question their environment and its layered history. Bus tours allow people to experience history in a collective way—and without monuments. And of course digital apps, as discussed, could be a way to harness already ubiquitous mobile devices to serve these aims in our city.

Sites/Histories: Case Studies of Commemoration

Our group chose case study sites to explore how commemoration might materialize to move forward some of the abovementioned themes and ideas. We chose sites related to displacement and social justice, and sites/histories that would allow us to explore different modes of commemoration. They are meant to serve as examples or templates as well as potential sites for consideration. Our three case studies are Chavez Ravine, the German émigrés of Los Angeles, and Black activism.

Chavez Ravine

Among the stories of displacement in L.A. history, Chavez Ravine looms large. It is the steep canyon northwest of downtown that in the early twentieth century became home to a cluster of three semirural Mexican American communities—Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop. The neighborhood had modest homes, a grocery, a church, and an elementary school. Some residents kept goats and chickens on the steep hillsides. These were poor yet cohesive communities. Many lived there because of residential exclusion from white neighborhoods. In the 1940s, the L.A. Planning Commission launched plans to build public housing throughout L.A. to deal with surging housing demand. Typical of urban redevelopment efforts of this era, it designated poor communities of color as “blighted” and targeted them for bulldozing to make way for redevelopment. Chavez Ravine was one of these communities. At first, the plan was to build a new, modernist public housing project designed by Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander. That plan was scrapped in the face of red-baiting by critics who charged creeping socialism.07 On the rise and fall of a public housing ethic in Los Angeles and its impact on the city’s built environment, see Don Parson, Making a Better World: Public Housing, the Red Scare, and the Direction of Modern Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

Though some families sold their homes to the City, others refused. By the late 1950s, a climactic battle between the City and the remaining residents led to their removal. The City ultimately sold the emptied land to Walter O’Malley, who built Dodger Stadium on the site. The former Palo Verde neighborhood is now covered by parking lots surrounding Dodger Stadium.

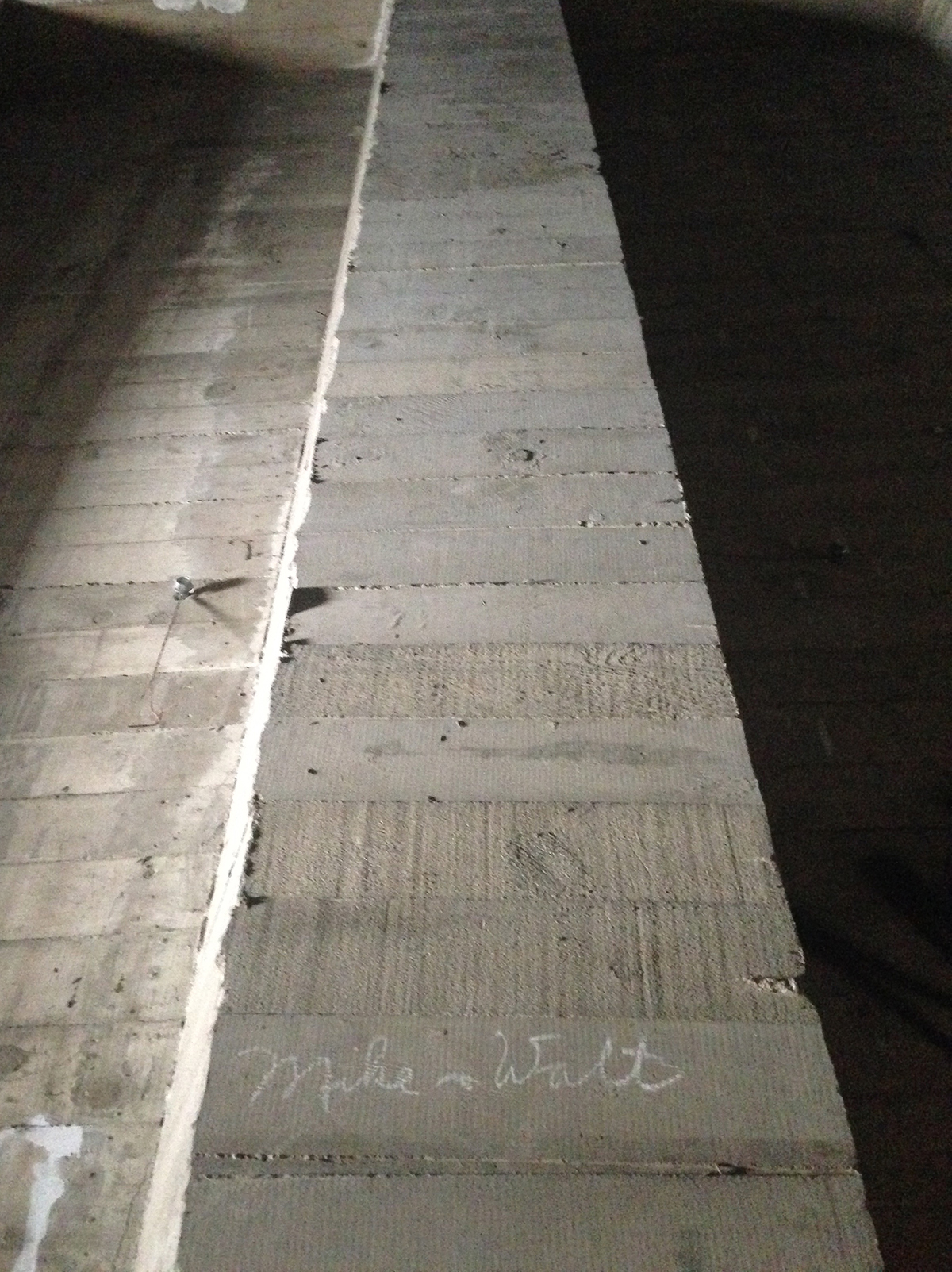

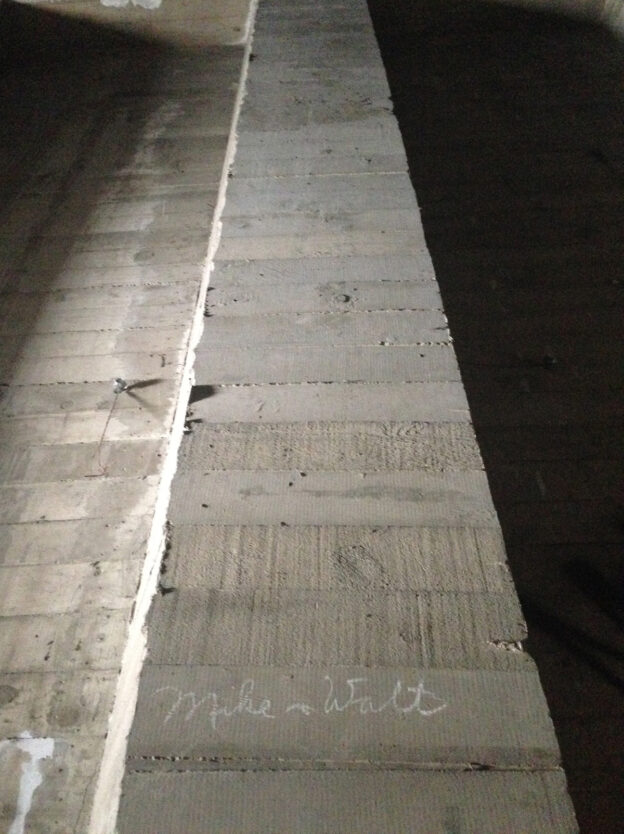

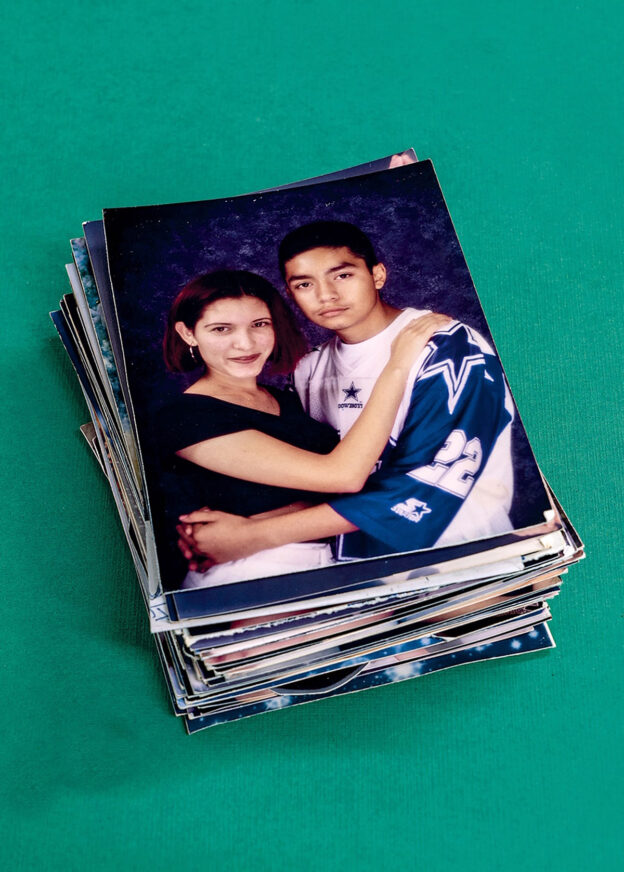

Every year, the displaced families of Chavez Ravine hold an annual picnic reunion at the Elysian Park Recreation Center. The only permanent markers of their experience are a small plaque outside the building, marking where the picnic happens, and a ghostlike set of stairs leading to nowhere. In their interviews with Priscilla Leiva for the “Chavez Ravine: An Unfinished Story” project,08 “Chavez Ravine: An Unfinished Story” website, undated, https://www.chavezravinela.com/home.

the families identify two priorities for commemoration: to convey this history to every individual who goes to a Dodger game, and to send the message that this should never happen again. Dr. Leiva shared that for some theirs is not a resentful narrative, but one that conveys “look at what we lost/sacrificed and look at what the city has because of us.” It is an affirmation of a displaced community that paid the ultimate price for the city we have today.

To commemorate the displaced Chavez Ravine community, our group devised a set of ideas that included ephemeral, internet-based, and permanent elements. One idea was to use the massive exterior walls of Dodger Stadium as screens onto which images of the Chavez Ravine community and its people could be projected. Fans entering or exiting the stadium would see images of the old neighborhoods (the Chavez Ravine elders have never-before-seen home movies and photos that they might be willing to share). The imagery might even reach deeper into the past when the land was home solely to Indigenous people. We agreed that the scale and spectacle of these projections would create a powerful space of civic memory, evoking an alternative sense of place by illuminating this layer of history.

Another commemorative tack might be to rename the streets and intersections around the stadium after the displaced communities. A plaque or wall located prominently inside or outside Dodger Stadium could explain the history of Chavez Ravine and list the last names of the displaced families. And another idea was to visually outline the Palo Verde neighborhood on the parking lot where it once stood, perhaps through a two-dimensional public art display. An app could even weave these elements together: it could tell a brief history of Chavez Ravine, identify the elements of memorialization (including the stairs to nowhere at Elysian Park Recreation Center), map out where the displaced families ended up settling, and highlight routes into Dodger Stadium through surrounding Latinx neighborhoods, all as ways to evoke the area’s Mexican American past. Fan sitting in the stands could open their phones and experience an augmented reality—a raised historical consciousness about the space around them.

The German Émigrés

Another case study on the theme of displacement and exile is the great influx of Central European émigrés in the 1930s and 1940s. Comprising Jews and leftists fleeing Nazi persecution, this group included important figures like Theodor W. Adorno, Vicki Baum, Bertolt Brecht, Alfred Döblin, Lion Feuchtwanger, Fritz Lang, Alma Mahler-Werfel, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Arnold Schoenberg, Salka Viertel, and Franz Werfel. When Germany invaded France in 1940, many non-German-speaking figures, like Igor Stravinsky, ended up in Los Angeles as well. They joined other German-speaking émigrés like the architect Richard Neutra. Later, some of the leftists found the atmosphere of the Cold War and McCarthyism intolerable and ended up going into exile once again. Thomas Mann, having become an American citizen, died in Switzerland. Their stories remind us of the fragility of democracy and the challenges of refugee life, even for celebrated authors and musicians. Commemorating their lives can bring those themes to the forefront at a fraught moment in American history and honor experiences that have receded from memory for many Angelenos.

Émigré life took place mostly in private homes on the west side, which puts potential sites of memory in private hands and makes creating public spaces impractical. The German government owns two important locales: the Thomas Mann house and Feuchtwanger’s Villa Aurora, both in Pacific Palisades. Because of the surrounding residential neighborhoods and the lack of parking, neither is a public site, although they do hold small events. The Rudolph Schindler house in West Hollywood is open to the public (under the auspices of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture), as is the Neutra studio in Silver Lake. University campuses also house a couple of commemorative sites: the Feuchtwanger Library at USC and Schoenberg Hall at UCLA. The Schoenberg family still has a vigorous presence in L.A.: the composer’s sons Ronald and Lawrence remain in the area, as does Ronald’s son Randol, a lawyer who has been active in the restitution of artworks stolen by the Nazis. And the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), through Stephanie Barron, its senior curator and a major historian of the emigration, fosters a strong awareness of the émigré experience.

In our subcommittee’s discussions about ways to commemorate the émigrés, the idea came up to install a small, permanent memorial at the Brentwood Country Mart, where many of them shopped. (A famous story tells of Arnold Schoenberg meeting Marta Feuchtwanger, Lion’s wife, there after Thomas Mann published his novel Doctor Faustus—a work that caused a dispute between Mann and Schoenberg.) Names could be inscribed in the sidewalk, on a plaque, or in a small exhibit. A driving app with narration tied to location, as described above, could tell stories of the émigrés as users visited their former homes. A bus tour of the homes—à la “Émigré Home Tours” (a playful variation on the tourist-popular Star Homes Tours)—with an open-roofed bus decorated for the occasion, was another idea for either an occasional or regular event to bring attention to the émigré experience. We also imagined a festival put on by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, a collaboration with LACMA in terms of an exhibition, or a collaboration on a conference or lecture series with the Thomas Mann House or Villa Aurora and one of the universities augmenting the group’s commemoration.

A final idea: there could be occasional displays of émigré faces, names, and quotations on billboards around the city, where one would expect to find a movie poster. This would have a certain ironic quality given the critiques of Hollywood commercialism that emanated from the likes of Brecht and Adorno. “The town of Hollywood has taught me this / Paradise and hell / can be one city. — Brecht.” “The whole is the false. — Adorno.” Such billboards would be mystifying to most people but could spark curiosity.

Black Activism

Black social justice activism has a deep, rich history in Los Angeles. To commemorate this history, we envisioned a multisite, multimode approach that would span the city, capturing the network of organizing. The Southern California Library could act as an anchor point for a series of explorations into this history. The library itself is rooted in the movement and could be woven into this commemorative project through exhibits, displays, and events. Murals could memorialize this history in a two-pronged approach—by commissioning new murals and by pointing people to existing murals. (An app like those mentioned above could facilitate this second goal.) One suggestion was to create murals on buildings located on former historic sites. For example, the site of the California Eagle newspaper is now an appliance and furniture store. A mural on that building might depict Charlotta Bass, the paper’s editor and publisher, sitting at her desk, glimpsed through a “window” into the interior. The former site of the Black Panther building on Central Avenue might also be a space for commissioned murals, public art, or a visual projection, depicting an organizing meeting or some other dimension of that organization’s history. People could also be directed to existing murals, such as the mosaic at Slauson and Crenshaw (now called Ermias “Nipsey Hussle” Asghedom Square) depicting Black history in L.A.

Another element of this commemoration could be reviving the Biddy Mason Park in downtown L.A. Born into slavery, Bridget “Biddy” Mason became a civic leader, entrepreneur, and philanthropist in the late nineteenth century. The park that commemorates her—which already features a timeline wall by artist Sheila de Bretteville and an assemblage by visual artist Betye Saar—might be updated to reflect new scholarship that more fully fleshes out Mason’s role in philanthropy and institution building in the city.09 Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Biddy Mason: Time and Place, 1991, sculpture, concrete and other materials, Biddy Mason Park, Los Angeles; Betye Saar, Biddy Mason’s House of the Open Hand, 1990, multimedia, Biddy Mason Park, Los Angeles.

Currently, the walk is not easy to find. This memorial is an example of an existing structure that could be updated and foregrounded more effectively—and ultimately woven into a larger Black history commemorative project.

Other ideas include walking tours in south L.A.; a plaque or other commemoration at the former Wrigley Field (42nd and Avalon), where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke and where the local War on Poverty program was headquartered; and a pattern of markers (such as plaques) marking other important sites. Once again, an app could identify and connect these various commemorations.