When I started doing the archival work known as Veteranas and Rucas in 2015,01 The archive is on Instagram as @veteranas_and_rucas, https://www.instagram.com/veteranas_and_rucas/?hl=en. See also the Project Statement on Guadalupe Rosales’s website, undated, http://www.veteranasandrucas.com/about.

the idea that the words “marginalized” and “underrepresented” would be used to describe a community and neighborhood I grew up in was strange to me. I felt pride in Los Angeles, where Latinx communities are heavily represented. This was obvious in my home, out on the streets, and in my intimate circle of friends. It was in the air, in the way we spoke, and in our swag. The thought of being underrepresented never crossed my mind. My memories of growing up in L.A. form a spectrum. Or: I had multidimensional experiences living here (and continue to do so). I love this city even though it has its rough moments.

I left Los Angeles very abruptly in 2000 when I was about 19 years old. Since the age of 16, I had lost friends and family to gang and state violence. Violence was at its peak in the 1990s. And since violence had been around me since I was little, I normalized it. But when my cousin was murdered in 1996, two days before Christmas, something in me awakened, pain I had never felt before. Because I was only a teenager when he was murdered, I knew nothing about grief, nor had resources that could help me heal. Luckily, I had family and friends who gathered in my home every day. We sat quietly in the living room or on my porch and reminisced and shared stories about my cousin. When I think back about these gatherings, I realize that this was my first collective healing experience, although there were also many sleepless and drunken nights involved. If I slept at all, I’d wake up exhausted from crying most of the night.

So in 2000, I moved far away from home, family, and community. As I grew older, I began to feel the distance of time and place. When I left Los Angeles, I also stopped all communication with friends and family. It wasn’t until the mid-2000s, when I reached out to my sister (who is a year older than me) for the first time since leaving L.A., that I started to reconnect. I asked her questions about childhood friends and parties we went to as teenagers. I asked her about family as well. There were friends who were doing well (although doing “well” can be subjective), who had become professional artists, who now had office jobs, who had kids and families. There were also those who ended up in prison or dead, and some who were caught between those two worlds. I was also using the internet to stay “up-to-date” with L.A., to have a sense of what was going on there.

Sometimes I didn’t know what to type into Google search. All I had were my own memories. I typed street names into Google Maps and searched for people I grew up with. Occasionally I came across articles about those who had passed away. One example was a high school friend named 02 Instagram, @veteranas_and_rucas, https://www.instagram.com/p/CBi1jeGJ1C3/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link.

I was shocked when I read his story in the L.A. Times.03 Times Staff Writer, “Claims Filed Against Police in Shooting Death of Boy, 17,” Los Angeles Times, Feb. 10, 1998. Another was Javier Quezada Jr.04 Daniel Hernandez, “Claim Filed in Fatal Shooting by Officer,” Los Angeles Times, Feb. 22, 2003. My friends were being murdered by the police. And if it wasn’t dehumanization of people of color, it was either criminalization or stereotypical clichés about growing up in Los Angeles.

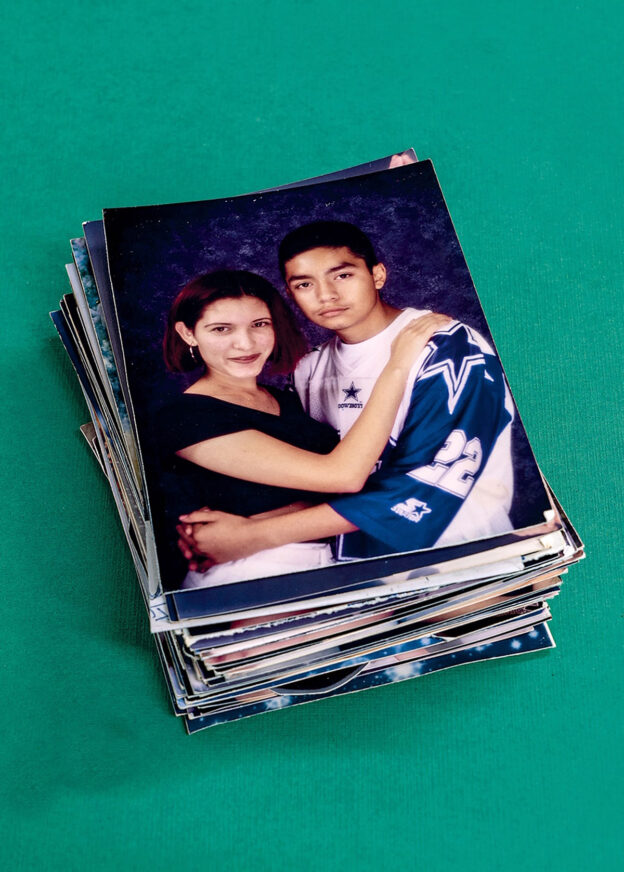

My time in New York is a big part of my story. I spent 15 years there and it’s where I became an adult. It’s where I found a new community of friends, mentors, lovers, and artists. It’s also where I came out as queer and was able to embrace myself in this way. But while I was living there, I felt like another part of me was missing. When I moved to New York, I brought a stack of letters and photos with me—of friends, boyfriends, siblings, and relatives. I held on to these photos and letters as something sacred. I kept looking at them and wondering how we can tell our own story. And I knew that I wasn’t alone in this desire to tell a story—not just my own, but a collective story of community and interrelated experiential bonds and pain and love and growth. I wanted to connect with people who were like me and to create a community-generated archive; I wanted it to be authentic and self-generating, embodying a shared experience where one story could amplify another. So in 2015, I started Veteranas and Rucas on Instagram, and then, in 2016, Map Pointz.05 Instagram, @map_pointz, https://www.instagram.com/map_pointz/?hl=en.

I began to connect and share stories with strangers and with friends whom I hadn’t seen or spoken to since high school.

The work and the sharing of those stories also encouraged me to come back home, so I moved back to Los Angeles in 2016. In the last few years, I have dedicated my life to preserving this communal history, from tracking down people (strangers, friends, and family) to acquiring Chicano/Latinx ephemera (like photos, flyers, letters, and clothing) and taking on the responsibility of preserving them as part of this story. Veteranas and Rucas began as an open invitation to various communities to share personal images and memories that create visual narratives celebrating identities and historicizing subcultures.

What has grown out of it, and now Map Pointz too, is a collaborative archive through which we can explore ideas about how history and culture are framed—and who does the framing. This work celebrates, humanizes, and reflects our shared culture’s positive and honest attributes. It creates space for collective healing and storytelling and finds ways for new dialogue to emerge about youth culture in Southern California that would not exist otherwise. I knew that it was important to preserve these materials and stories—not just my own but those belonging to hundreds of others—to counteract what I now understood to be the underrepresentation, misrepresentation, and historical erasure of Latinx communities in Southern California.

It all manifested through grief, memories, and urgency because of the ways in which my community and I were seen from an outsider’s perspective. The more engaged and serious this work became, the more I discovered. My aim was also to find potent revivals of my culture as well as generate unexpected connections between seemingly irreconcilable institutions and communities. These projects provide a reflective surface to see oneself—not through an act of vanity but through affirmation and validation.

Collectively, we have cracked a code. We’ve figured out a new approach to representation and memory through this sharing and sifting of images. My culture is so beautiful and complex that it’s almost impossible to share stories in a linear way.