Carlos Diniz, born of Brazilian parents, spent most of his childhood in Los Angeles making art in almost every medium available to him. Drafted into military service at 18 years old in 1946, he was posted overseas in Venice, Italy, where he began to marry a fascination with architecture and city scenes to his love of drawing. Once his service was over, Diniz earned his B.A. in specialized design at Art Center College in Los Angeles in 1951, undertaking a self-education in architecture along the way. He then joined the Viennese architect Victor Gruen’s team developing promotional materials for Gruen’s large-scale, pioneering shopping center schemes. In 1957, Diniz opened his own architectural illustration firm, Carlos Diniz Associates Visual Communications, first in the Granada Building and later in Chapman Plaza.

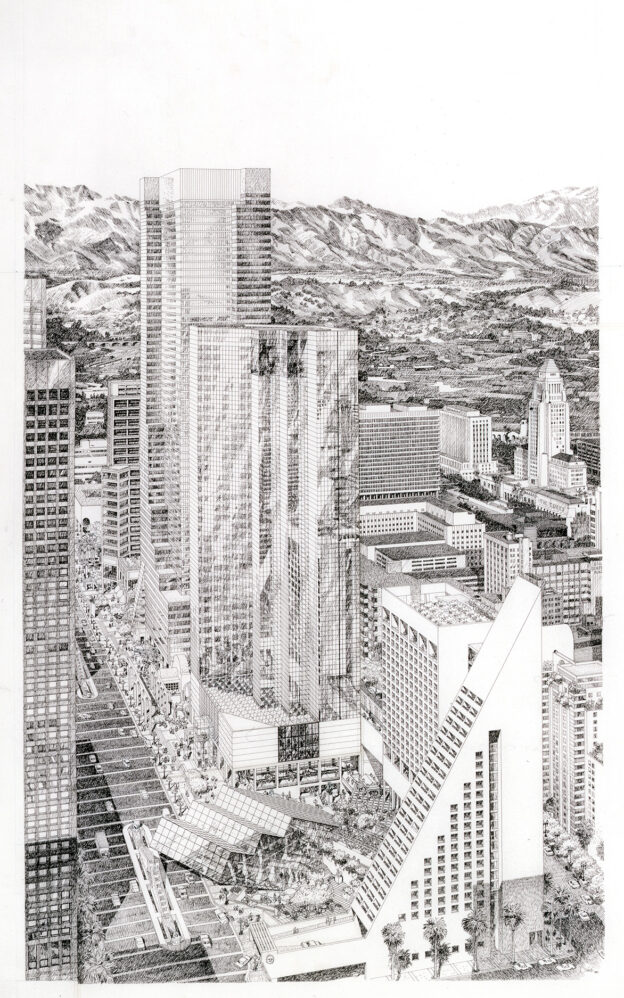

One of the last to master the tradition of the hand-drawn building perspective, Diniz became nationally known over his four-decade-long professional career as an architectural delineator who could translate architects’ often very technical renderings of proposed buildings or entire new communities to a format easily understood by clients, developers, review agencies, and the public at large. Diniz called his work the “art of illusion,” and he innately understood how to articulate, even choreograph, how these yet-unbuilt projects would be perceived. Focusing on the birds-eye view and on spaces, vistas, and movement between structures, his professional practice traces the development of Southern California and beyond in the postwar era. He made every drawing accessible, using his skill to seduce its viewer into embracing the architect’s scheme.

Diniz’s early clients included the prominent architects Welton Becket and César Pelli, and he collaborated with Frank Gehry under Gruen. Over time, his practice expanded nationally with his work for the giant firms of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM) in San Francisco and HOK in St. Louis. He also was integral in helping design Minoru Yamasaki’s World Trade Center in 1961 and the L.A. landmark Century Plaza Hotel in 1964. Diniz worked on thousands of projects around the globe for some of the world’s best architects. Thanks to a gift from his family in 2016, the vast archive of work by Carlos Diniz Associates became part of the Architecture and Design Collection held by UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum.

This archive gains a particular meaning when considered in a volume, like this one, dedicated to reconsidering the civic memory of Los Angeles. Diniz’s work is a reminder of just how many approaches to imagining the future (architectural, cultural, or otherwise) were pioneered or given room to roam in Southern California. (His had a painterly, hand-drawn aspect that helped leaven the futurism with craft and a particular, recognizable personal style.) That history of speculation in Los Angeles, even that anxiousness to move into the future, is a legacy worth understanding and preserving just as any significant work of architecture is.